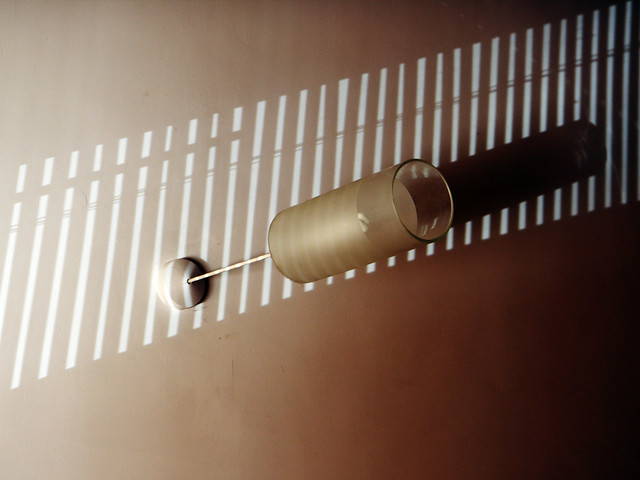

Last weekend I wandered down to Southwark Street armed with my camera to see the melting house. I wasn’t sure what I could expect to see, how much of it would be left (almost all of it, as it happens), how big it would be (close to full scale), how near I’d be able to get (3-4 meters, dodging all the other spectators) or, like all public art, what its surroundings would be like (pretty ugly) and how they’d affect my photography opportunities. When I got to the installation the light was going (due to a bus-related mishap), so all in all I was pretty ill-prepared kit-wise and the images I had in my head were not achievable.

I was forced to think about what exactly it was I’d hoped to capture. Most often, we think of photography as a means of recording reality, but unreality is a theme that photographers utilise in every step of image creation. Stories are told through meticulously staged scenes with props and carefully crafted lighting, images edited and post-processed, perhaps even composited from many captures a la Jeff Wall‘s complex cinematographic works. When we look at a photograph what we see may never have existed.

I am fascinated by this kind of work, but in my own photography I rarely alter or stage a scene, or do any post-processing at all (I’m sure there are times when I really should). I am interested in a different kind of unreality; the idea that as soon as an image is captured the way it’s viewed is detached from its setting.

With any given subject I quickly begin to look for ways to make it appear different than it is, out of context, isolated or abstracted. I find myself honing in on an interesting pattern in a boring view or maybe the decay in a beautiful scene. I like distorting perspective with wide angles and telephotos to add drama or miniaturise. But always shooting exactly what’s there. I like my images to offer an unreal perspective on reality, pose questions and maybe be a little confusing. I am less interested in the narrative in my own work.

My photos from the melting house were not amazing (I’m going to blame the dusk) but I like that the installation itself echoes the ideas I’ve described: A hyper-realistic model of a familiar object made from a material that’s equally familiar, but completely out of context. I hope that I’ve captured that at least.

Alex Chinneck’s ‘A Pound of Flesh for 50p’ installation is at 40 Southwark Street, London, SE1 9HP until 18 November 2014